Aoileann lives on an island, a slab of rock partly submerged like a sunken ship. Her life consists of helping Móraí take care of her bedridden mother, but she dreams of escaping the island one day. Whenever she leaves the house, islanders look at her with a hatred bordering on fear and she doesn’t know why, but she knows that it’s connected to her mother’s illness. Móraí and Dada refuse to give her any answers, but sometimes she sees the same look in their eyes. And then she meets Rachel, an artist from the mainland who has just arrived with her newborn baby Seamus, and who doesn’t look at her that way. Rachel, kind, motherly and friendly, soon becomes the object of Aoileann’s obsession.

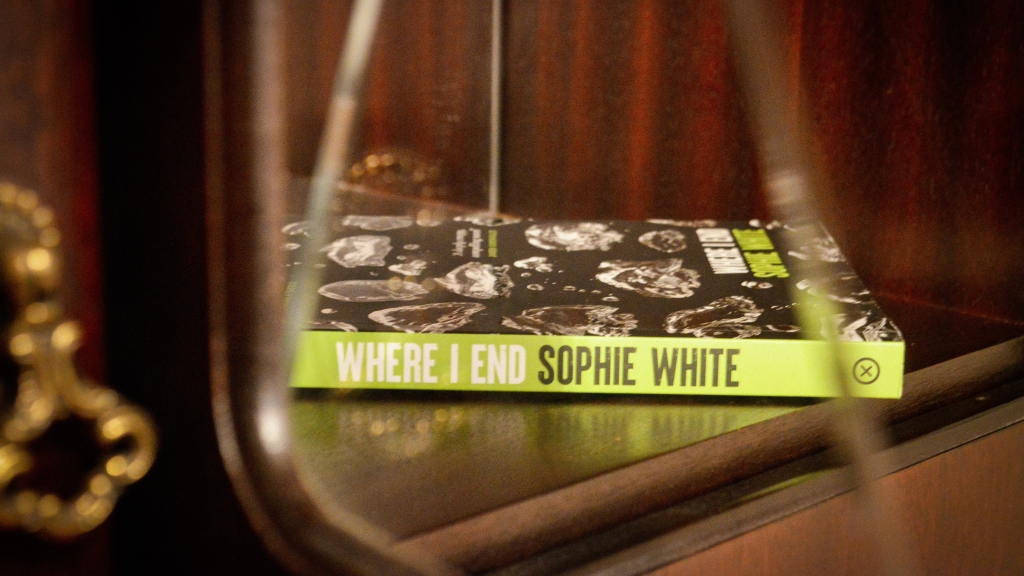

Thus begins Sophie White’s fourth novel, Where I End. Narrated in the first person from the perspective of 19-year-old Aoileann, the story unfolds slowly as she takes us through the island, her weather-beaten doppelgänger of black, polished stone (Aoileann, after all, means “island”). Different to her previous works of fiction, which are on the humorous side, Where I End has more in common with the topics addressed in The Creep Dive, the famous podcast which White co-hosts, as the novel goes from an eerie mystery to full-blown horror. The style and main character also echo Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle and pay homage to many popular horror tropes.

The setting is one of the most interesting aspects of the novel. Aoileann’s home is inspired by one of the Aran Islands, Inis Meáin, where Sophie White spent some time writing. In the novel, the island is a godlike mass of stone that holds its inhabitants captive with some evil influence: “I don’t like that what I can see of the island is only a sliver of its full, awful self. […] I must stay vigilant. I must keep the submerged part of the island in sight”. Like the hidden part of the island, there is something wrong with Aoileann, but where does it come from? Has it always been there?

The novel, like many of its genre, asks questions about the genesis of evil, but most interestingly, it grounds them on corporality. Characters, including the island, are described above else as bodies: stone bodies, able bodies, full bodies, nourished bodies, bodies that feed, bodies that die, and bodies that are sick. Breastfeeding and food consumption are recurrent images throughout the novel, and they tell us there is something else to be had from food apart from nutrients: companionship and guidance, intimacy, satisfaction— all the things Aoileann lacked and almost forgot about until she met Rachel.

Aoileann, now quiet, cruel and lonely, once craved her mother’s affection and envied other children, but as time went by, she substituted her sadness and self-pity for something else: “over time, my long-held hurt began to be replaced with something altogether more uncomfortable. The Something frightened me. I didn’t learn the word for it for a long time.” Aoileann’s needs are above all physical: touch, affection, and nourishment, and the novel seems to suggest that questions about evil might be ridiculous if we have not before explored the corporality of human relationships and interactions. The word for the Something within Aoileann might be dorcha (“The islanders use this word for all kinds of darkness”) and we see it grow bigger and bigger, as her desire for Rachel increases and she starts plotting ways of taking Seamus out of the picture and devises torture routines for her silent mother.

But this dorcha is not only within Aoileann . It infects everyone, including Rachel, through whom White returns to many of the issues she wrote about in her memoir Corpsing. It is Rachel’s battle with postpartum depression and her struggles as she juggles work and motherhood that send her spiralling into Aoileann’s arms. And Aoileann, as we know, has intentions not only to care for her but to possess her in a desperate attempt to find both a mother and a lover. Motherhood, grief, loss and body horror come together in a chilling, present-tense narrative that keeps tensions high throughout.

Where I End is a well-paced, deeply disturbing tale, packed with little mysteries —What happened to Aoileann’s mother? Why won’t anyone talk about it? Why do the people in town call her nil sí beo (she doesn’t live)?—that, although not completely resolved, make it a compelling read and a successful entrance into a new genre for White. Although Aoileann experiences some developments as the pilot advances (she defies Móraí and becomes more fearless and cunning), by the end of the book she is established as an evil character rather than a complex one, and we are left to wonder if both she and the island are just monsters that need to be fed.