I once read somewhere that all literature could be divided into two categories: one that points out everything that is wrong, a diagnostic kind of literature, and one that heals. Over the years I have, sometimes unconsciously, categorised my favourite books into the second kind, because I believe great literature always has a healing quality — it doesn’t have to be pretty, and it doesn’t have to answer any questions, but it has to offer some kind of catharsis and some kind of hope, if only in language as a means of sharing human experience with others. This has been my experience of reading Tommy Orange’s work.

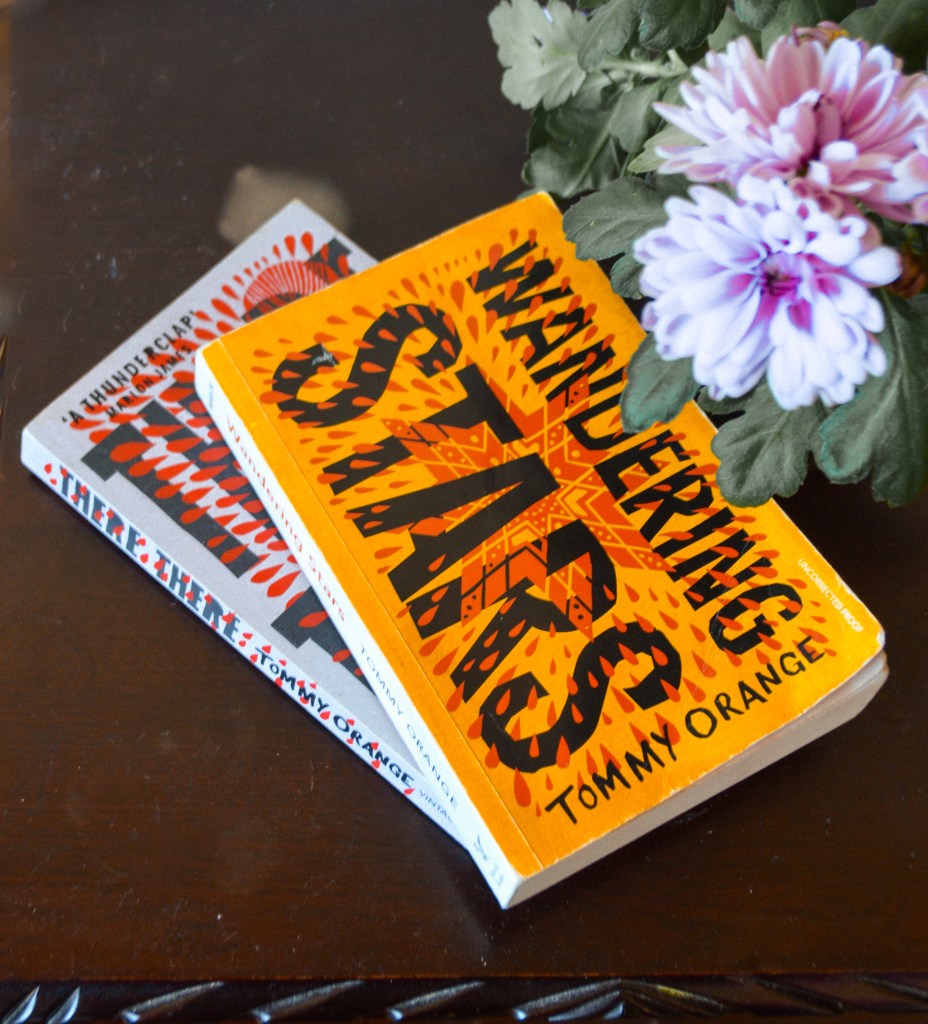

In order to heal, you need to know what’s wrong first, address the pain and locate the wounds. Yet when it comes to historical wounds and trauma, the diagnosis can get complicated. For the characters of Orange’s new novel, Wandering Stars, as for many Native Americans these days, the wounds have been open for centuries, and the enduring effects of colonisation, violence and systemic marginalisation continue to reverberate strongly.

Loother, Lony and Orvil are three teen brothers from Oakland, California, who lost their mother to addiction and are now under the guardianship of their grandma, a recovering alcoholic, Jacquie, and her sister Opal. Orvil, who was one of the characters in Orange’s debut novel There There, is grappling with the aftermath of being shot at a powwow in Oakland. The bullet, still lodged in Orvil’s body serves as a poignant metaphor for contemporary America’s afflictions, including the opioid epidemic, leading to his dependency on painkillers. More significantly, that the bullet can’t be removed mirrors the persistence of generational trauma and historical wounds—a constant reminder of violence, fear, and the identity crises that Native American youths confront after centuries of cultural and linguistic neglect.

Much like There There, which pulsates with polyphonic energy, Wandering Stars introduces a diverse array of characters whose stories are interwoven across time. Tommy Orange intricately constructs a genealogical narrative stretching from the Sand Creek massacre, as experienced by Orvil’s great-great-grandfather, through a century of struggle, resilience, and survival, all the way to contemporary California. Orange’s characters resonate with vitality, love, passion, grief, and anger; they grapple with their past and future, recognising the profound interconnection between the two. In navigating a system rigged against them, their bonds with each other and with their ancestors become indispensable. Orange deftly illustrates these connections, portraying characters who, knowingly or unknowingly, echo their ancestors’ actions and partake in the healing of generational traumas as they navigate their place in the world. This thematic exploration aligns beautifully with the novel’s title, portraying each character as a wandering star, finding their place within a constellation of meaning

Reading Wandering Stars is a deeply moving experience. The prose is consistently dynamic, with each chapter offering a new voice, perspective, and temporal setting. Yet, it’s also profoundly painful, offering an unflinching acknowledgement of some of history’s most agonizing episodes. The trajectory of the bullet, meticulously traced over a century, encapsulates this history in a hauntingly vivid manner. However, for Orvil, the focus is less on removing the bullet and more on embracing it—learning to live, make sense of, and even dance with the bullet that remains lodged within him.