Eileen is out today and here’s why Ottessa Moshfegh is one of the most relevant writers today.

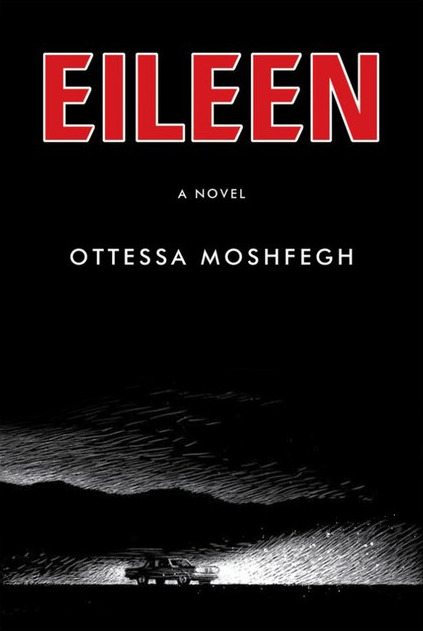

The adaptation of Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2016 novel Eileen hits the cinemas today and I am very nervous. Eileen is one of my favourite contemporary novels and I fear that everything that is wonderfully uncool and ugly about it will be glamorised in full Hollywood style— although William Oldroyd, the director (who also directed Lady Macbeth, 2016) seems up for the challenge. I’ll be sure to share my thoughts on the movie once I watched it, but this is a great time to discuss why Eileen and the rest of Moshfegh’s fiction are very high up on my list of contemporary literature.

Moshfegh is not the first author to be thrown into the “female rage” category. Angry women, crazy women, unlikable women…Specifically in literature, terms like “unhinged female character” and “female rage”, or quotes like “I support women’s rights but most importantly I support women’s wrongs”, have made their way into online mainstream culture, used ad nauseam on the bookish corners of social platforms like BookTok or Bookstagram. They often allude to female characters who commit horrific and heinous acts, such as murder and cannibalism, but do so in a glamorous way, dressing to the latest fashion and more often than not, looking like supermodels. Although the phenomenon has its roots in a decades-long fight for bringing complex and realistic female characters to the page, it has been somewhat simplified and over-glamourised. In the middle of it all is Ottessa Moshfegh’s third published book, My Year of Rest and Relaxation(2018).

Born in the United States to Iranian and Croatian parents, Moshfegh has focused her writing on losers and underdogs. Her characters are often driven to extreme cynicism and nihilism, they are often disgusting and unlikable and they are, more often than not, female. Her divisive fiction and enigmatic personality have earned her a devoted fanbase of young women who define themselves as “sad girls”, but her work has also been met with brutal criticism for her grotesque, disturbing and morally questionable characters.

Moshfegh’s leap to fame came with her first published novel Eileen in 2015, which won the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award for debut fiction and was shortlisted for the 2016 Man Booker Prize when she was only 34 years old. The novel centres on a 24-year-old woman who works as a prison secretary in a small suburb of New England during the sixties. Eileen hates her life (which mainly consists of caring for her alcoholic father), her job and her body. Through her eyes, the reader is introduced to a monologue of contained rage, repressed sexuality and pathetic fantasies of self-harm, mayhem and murder. However, Eileen is not a villain, just a lonely girl born to unfortunate circumstances, catapulted by a newly arrived coworker on a journey of self-discovery and crime, involving very unpleasant subjects and constant mentions of enemas and rape. On top of this unpalatable plot, the self-loathing protagonist goes on lengthy, graphic descriptions of her use of laxative pills. It is no wonder readers labelled the book as gruesome and grotesque, but online reviews and vlogs about it were hyper-focused on Eileen being disgusting, a term that at the time seemed unforgivable in a female character.

These less romantic aspects of human existence were already becoming a defining attribute of Moshfegh’s fiction. Even before Eileen, she tried her hand at another disgusting character, this time a male, in her debut novella, McGlue. The novel is set in Salem, Massachusetts in the 19th century, so the characters’ lack of hygiene is somewhat justified, but the drunken and violent rages in which the main character, a sailor, often finds himself are nothing short of gory and visceral. Although the reviews of the novel do mention its violence, the physical attributes of the main character are not the focus of the discussion; McGlue is even described as a hero by the LA Times, despite the premise of the novel being that he probably murdered his best friend, while Moshfegh’s female characters are usually described as anti-heroes or just “unlikable female characters”.

When Eileen came out, Moshfegh was surprised at how unforgiving readers were towards her protagonist, who despite her dire circumstances manages to escape her miserable life and finds solace and self-acceptance in her newfound freedom. During an interview with The New York Times in which she is described as an “author-provocateur”, Moshfegh admitted to being baffled by the response: “They wanted me to somehow explain to them how I had the audacity to write a disgusting female character.” Even her agent at the time, Bill Clegg, commented on how hard it was to get the novel published, as people were “really turned off” by the main character.

What did readers find so repellent about Eileen? Unlike McGlue, she is not a murderer, and definitely not as villainous or treacherous. She is, however, addicted to laxatives, average-looking, and keeps a dead rat in the glove compartment of her old car. Perhaps more damningly, she is just not shy about any of those things, and quite forward in her approach to the world. At the core of her novel, Eileen comes across as a deeply vulnerable girl that, just like the rest of Moshfegh’s characters, hides a yearning for something unknown and possibly unattainable behind a masque of misanthropy and nihilism: “I deplored silence. I deplored stillness. I hated almost everything. I was very unhappy and angry all the time. I tried to control myself, and that only made me more awkward, unhappier, and angrier. I was like Joan of Arc, or Hamlet, but born into the wrong life—the life of a nobody, a waif, invisible.” But it was none of those qualities that readers engaged with.

In her next novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018), Moshfegh purposely made her protagonist look like a supermodel. Unsurprisingly, it became her best-selling book and the one that earned her a devoted and cult-like fanbase of young women who, like her unnamed character, wanted to hibernate for a year. The timing for My Year of Rest and Relaxation was perfect too, as the novel, which is mostly about self-isolation, came out during the pandemic. Outwardly, the protagonist is the opposite of Eileen: she is a beautiful and rich twenty-six-year-old who owns an apartment in Manhattan. She studied Art History at Columbia and works in one of Manhattan’s most exclusive art galleries. She has it all, but she is still miserable: her parents are dead, her friends are awful and her only relationship is with a corporate man who only calls her for terrible sex. But she has a plan: hibernating for a year in hopes of rewiring her brain so that it can work properly. Despite the glamorous setting, this Sleeping Beauty still behaves in a very moshfeghian fashion: she takes a shit on the floor of the art gallery, barely showers, spends her evenings ordering takeout, watching porn movies and fantasising about Whoopi Goldberg’s vagina for comfort.

Like Eileen, the protagonist of My Year of Rest and Relaxation yearns for another life and for true connection, directly echoing something Eileen says: “the idea that my brains could be untangled, straightened out, and thus refashioned into a state of peace and sanity was a comforting fantasy.” However, her portrayal as a beautiful woman somewhat alleviated her grotesqueness, a dichotomy that operates in Moshfegh’s work on different levels: “My writing lets people scrape up against their own depravity, but at the same time it’s very refined . . . it’s like seeing Kate Moss take a shit”, she said to an interviewer. Both characters manage to immerse the reader in a whole new set of values, a world in which the grotesque and the uncool are the new currency, for despite their looks, they are always society’s rejects and underdogs, depraved in many ways, which might be why many readers refuse to sympathise with them. In the age of likability and relatability, My Year of Rest and Relaxation found a more forgiving audience than Eileen.

Both books came at a time when “unlikeable female characters” and “female rage” were becoming just another genre. Just a quick online search will come up now with plenty of reading lists like “hot girl summer reads”, “badass women books”, “best female rage reads”, etc. that feature both. The way in which mainstream media made a token out of these characters became a concern for Moshfegh, who expressed her worry over her readers finding the idea of hibernating for a year on sleeping pills so appealing. But just when it seemed like Moshfegh would fall right into these new boxes that have proven so lucrative for publishers in the last couple of years, she began to steer away from that direction.

Before the success of My Year of Rest and Relaxation faded, Moshfegh published a mystery novel she had been working on for years. Death in Her Hands (2020) follows an elderly woman, Vesta Gul, who moves to a cabin in the woods after her husband’s death, with her dog. On a walk in the woods, Vesta Gul finds an enigmatic note: “Her name was Magda. Nobody will ever know who killed her. It wasn’t me. Here is her dead body.” Thus Vesta takes on an investigation into Magda’s death. Isolated, paranoid and finally free from her husband’s controlling presence, the first-person narrator slowly spirals into madness and obsession, deviating from the classic whodunnit structure into a character study. Although the novel earned her some comparisons with Nabokov’s style, for which Moshfegh expressed her delight, it was not met with quite the same enthusiasm by readers, even when Vesta shares many qualities with Moshfegh’s previous characters: she is an unreliable narrator, she is angry and abused by men, cynical, cunning and witty, but still a loner. Perhaps she’s just not that glamorous, but Death in Her Hands still made it to some Goodreads “female rage” reading lists. Anyway, by then it was clear that Moshfegh was more interested in defying labels than in keeping her fanbase happy.

Lapvona (2022), Moshfegh’s latest novel, is set in medieval times and follows a group of very different characters in a village ruled by a narcissistic and cruel tyrant named Villiam. Further distancing herself from her previous work, Moshfegh ventured outside of the first-person narrative to try her hand at an eerie, omnipresent and impersonal narrator that flows through each of the characters’ minds. However different Lapvona might be, it remains disturbingly grotesque: characters maul each other to death, people eat cow manure, elderly women breastfeed grown men. But it was not the graphic violence and gore that baffled critics and readers alike, but the nonsensical existentialism of the book. Lapvonareads like a fairy tale and at first appears to be a fable about contemporary America—there is, after all, a narcissistic tyrant feasting while the rest of the village starves—, but as the novel advances it becomes clear that the story is not a metaphor for anything, but rather a trippy and grotesque Thus Spoke Zarathustra, where the characters just sink deeper into violence, carnage, mommy issues and despair. Many critics slammed the book as pointless gore, while others took it as a political joke, but Moshfegh remains inscrutable about it, driving all the interviews towards her technique and refusing to talk about interpretations of the novel.

Despite their apparent cynicism and anger, Moshfegh’s characters are not nihilistic. If there is something they all share, from the short stories to the enigmatic Lapvona, is a constant yearning for connection. The stories in Moshfegh’s acclaimed collection Homesick for Another World (2017) condensate many of the author’s motives and interests. In the stories, a set of strange characters navigate life from their very own particular yearnings: a little girl is convinced she comes from a different reality to where she could go back to if he kills the right person on Earth; a young man haunted by his pimples and his small hands exposes himself to women with the hopes someone will finally tell him he is beautiful; and an alcoholic Catholic-school teacher hopes to be absolved from her sins—“I wanted a little tenderness, I think, and I imagined the priest putting his hand on my head and calling me something like ‘my dear’, or ‘my sweet’, or ‘little one’. I don’t know what I was thinking. ‘My pet’”. The book is filled with self-inflicted violence, drunkenness, murder and grotesqueness, and yet the pathetic search of the characters for connection or meaning borders on the sublime.

For Moshfegh, there is no metaphysical bubble where the sublime and the beautiful operate, there is only the physical and, as she has said in several interviews, she is not concerned with writing “grotesque fiction”. She has even said she doesn’t even notice how grotesque her work is until she reads it out loud. What she is concerned about is writing characters that feel real, and there’s no way to write about them without writing about their bodies; her motto is “Let me not forget that I’m a human being”. Going into detail about a physical reaction— from rashes or diarrhoea and self-induced vomiting— says a lot about them psychologically and even spiritually.

While reality violently penetrates her novels — there’s gun violence in Eileen, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends with a broadcast of the WTC towers crumbling down, and Lapvona is about a tyrant—, her books remain grounded in the physical experiences of people, which makes it very hard for her to fit any label. Beyond likability and rage, even beyond gender, Moshfegh seems more preoccupied with bringing the physical experience of flawed humans into the page, thus eliciting a physical reaction from the reader in return. It was Kafka who said that a book should be “the axe for the frozen sea inside us”, and if we agree that literature should pierce through that thick layer of stability and contentment, there’s no doubt that there are few contemporary authors who can make readers as uncomfortable as Ottessa Moshfegh, whose resistance to be labelled far exceeds her fondness for the grotesque when it comes to making readers uneasy.